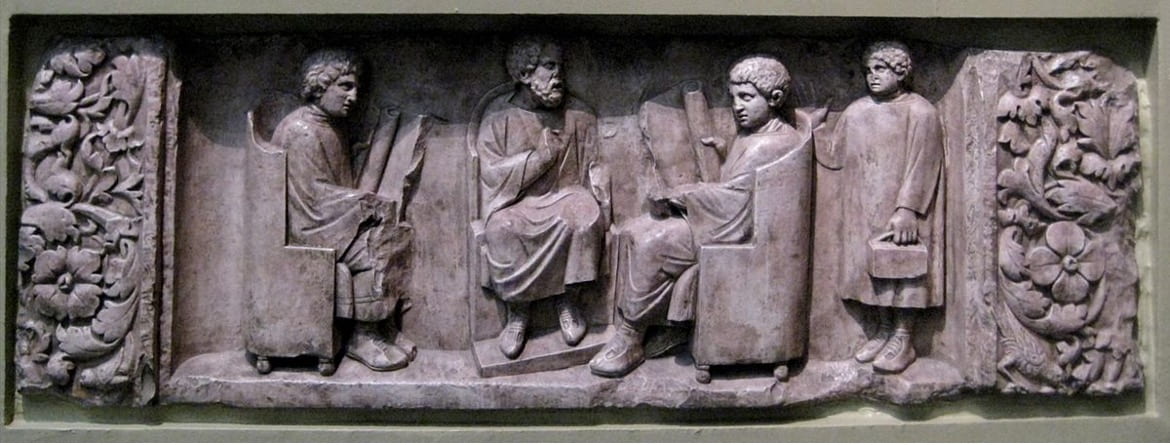

Photo: relief found in Neumagen near Trier depicting a teacher with three students (180-185 CE). Credit: Ancient History Encyclopedia

“When You Set Out for Ithaka…”

By Margaret Dunn

When I was ten years old, my grandfather gave me a copy of Mary Pope Osborne’s Tales from the Odyssey as a birthday present. He was an English professor, so gifts such as this one were not uncommon. Every year I’d receive a new paperback or two, plowing through each title so that I could answer his questions at Christmas. That year, when I unwrapped my birthday gift to find Tales from the Odyssey, I thought it to be just another attempt to instill his own love of reading in his grandchildren. I expected to trudge through it and treat it as I had the others – yet within the first few pages, I was hooked, lost in a world of heroes and cyclopes, magic and monsters.

Needless to say, my grandfather was delighted, promptly returning to Barnes & Noble to purchase every book on myth and antiquity written for ages eight through twelve. I devoured them all just the same. At his insistence, I then decided to enroll in Latin in middle school – but I found the first few months to be nothing short of upsetting, frustrating, and challenging. The grammar rules blurred together, vocabulary shot in one ear and out the other. How can two declensions not be enough? I’d wonder. Hold on, now you’re telling me there’s five? In addition, I was exceedingly shy at the time, rarely speaking in class. Being forced to translate aloud was utter torture, and I even found asking my teachers for help to be a struggle.

My grandfather, on the other hand, was perhaps the most outspoken person I knew. He could talk to anyone: waiters, cab drivers, the stern-looking police officers in Grand Central – anyone he happened across while on his daily stroll through the neighborhood park and, of course, his students.

My mom and I feel that my grandfather was always meant to be a teacher. He could find commonality with anyone and hold entire rooms at attention with a simple anecdote or an account of his latest trip to the grocer. He also had a particular fondness for tweed – but as the son of immigrants, being a professor didn’t always seem to be in his cards. Growing up, his family was exceedingly poor, and he was fortunate enough to earn a scholarship to attend school in New York City. There, he found reading in both English and Latin to be an escape from the struggles he faced at home, and several years later, he made his way to college as an English literature student, the first in his family to attend university, later the first to earn his Ph.D. and become a professor.

Back in middle school, I used to sit in on his lectures while he taught the Odyssey at Fairleigh Dickinson University. I remember being struck by his passion, as well as by how much he enjoyed conversing with his students after class. His enthusiasm was infectious, and for the students, his classroom was a place for cultivating curiosity and, in turn, satisfying it.

Slowly, I began to view my own Latin classroom not as a stage on which to stutter out a flawed translation of a line from the dreaded textbook Ecce Romani, but rather as a place to try and to learn – to fail and to go again. Flashcards were made, vocabulary lists drawn up, office hours attended. With hard work, as well as encouragement from my grandfather, my outlook and my experience both began to brighten. The Latin classroom soon grew to be my favorite place, remaining that way through my graduation from high school six years later.

As my passion for the language grew, my Latin curriculum soon became a favorite topic of conversation between me and my grandfather, whether over turkey legs at Thanksgiving or around the tree come Christmastime. Throughout these conversations, as my attitude changed, my perception of classics itself began to shift, too. The excitement I’d felt about the monsters, adventures, and heroes I had seen in the pages of Tales from the Odyssey evolved into my fascination with the ancient world at large – its languages, its cultures, its stories.

At each family holiday, my grandfather would ask me what I was reading, then always reply with the same comment: Just wait, just wait ‘til you get to the Cicero, the Ovid, the poetry. During my freshman year of high school, I remember excitedly remarking to him over the phone that we had just begun Cicero in Latin class, and that I could now rattle off an epitaph or two in attic Greek, which I’d picked up that year. Delighted, he had me repeat those lines of Greek, this time with his tape recorder in hand.

My grandfather never got to hear about Ovid or the poetry, though, as he passed away in my sophomore year of high school. Sometimes, I think about the conversations we never got to have, the museum trips we missed and the Thanksgiving meals we didn’t share. Recently, I’ve been imagining them more often, having just declared my double majors in Classical Studies and English. I think about what it would have been like to call him with the news, hearing his warm laugh on the other end of the line. I’m sure he would have then asked to see my notes from class that day, as he always loved to do.

I remember sitting beside him in our living room a few months into my first Latin course nearly ten years ago, Ecce Romani lying open in my lap. He peered quietly over my shoulder, having asked me to read him a passage out loud. I stumbled out the first phrase, expecting the anxiety and dread that usually accompanied translating to take hold of my chest. But it never did. Beside me, my grandfather was smiling, gently nodding as I searched for the verb, found the subject, and strung it all together. His quiet encouragement allowed for that pressure I often felt – pressure that was only heightened by my shyness – to fade away.

Recently, I’ve experienced a new longing for his advice. For the first time in my life, I feel as though I cannot see what steps lie ahead in the journey before me: two more years of college, graduation, and then … ? In high school, the “real world” felt so far away, but now, despite still having several years left at Penn, I find myself grappling with the worry that any decision I make could be the wrong one – that any choice taken, or not taken, could result in doors closing permanently, leading me along a path that I regret.

I imagine what he would say in response to these thoughts. My grandfather was always so much more articulate than I am, always able to approach things from a different perspective, moving the framing of a lens that most people thought to be fixed. The smaller details often struck him – even the little things, which I would write off as insignificant. If he could hear me now, I believe he would tell me to have a little more faith, to enjoy and embrace the journey regardless of its uncertainties. In words as timeless as Homer’s, he’d explain that encountering monsters and vengeful deities along the way is inevitable, no matter the route taken. He would encourage me to cherish the calmer waters, taking time to walk the beaches of lands familiar and unfamiliar – even when storm clouds appear to gather overhead.

Perhaps what he’d stress the most is that I hold close the moments that I share with the people I meet along the way: the dinners had, stories exchanged, gifts given, the times when strangers became friends – all that I’ve experienced and all that is to come. With a little faith, he’d tell me, the journey will be made, even if it’s dotted with these moments of feeling lost and directionless – it will be made all the same. Eventually, I’ll realize I’ve made it to the shores that I will call home.

Photo: the author’s grandfather, Professor Peter Mullany. Credit: Margaret Dunn

Margaret Dunn (College ’23) is a student at the University of Pennsylvania studying Classical Studies (Classical Civilizations) and English.

Comments? Join the conversation on our Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn!