An Analysis of Fifty Days at Iliam

By Lily Nesvold

Fusing ancient storytelling and modern art, Fifty Days at Iliam is a ten-part canvas painting that uses a mixture of oil, crayon, and graphite. Based on Alexander Pope’s translation of Homer’s Iliad, it is permanently on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This unique installation recalls a story that everyone knows, classicists and non-classicists alike, and its expression packs so much meaning into so few brushstrokes.

The creator, Cy Twombly, was an American artist experienced in painting, sculpting, and photography. He was interested in Greek and Roman mythological storytelling and wanted to visually represent such complex and rich history in an accessible format. He unfortunately passed away in 2011.

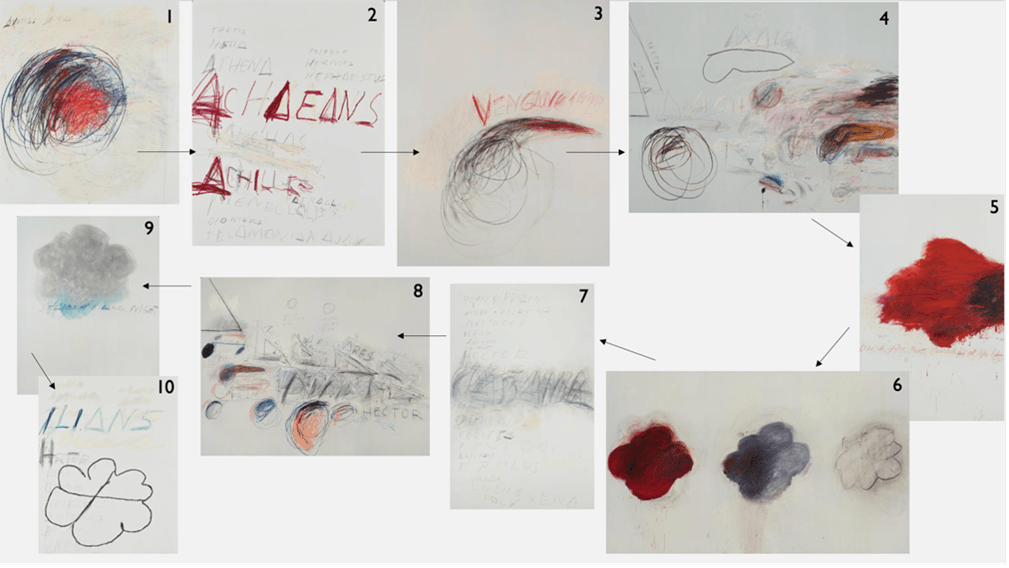

Order of the installation: (1) Shield of Achilles, (2) Heroes of the Achaeans; (3) Vengeance of Achilles; (4) Achaeans in Battle; (5) The Fire that Consumes All Before It; (6) Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector; (7) House of Priam; (8) Ilians in Battle; (9) Shades of Eternal Night; (10) Heroes of the Ilians

Though the paintings have an order in which they should be viewed, the installation conveys the sense that this order is not set in stone. An observer first sees the Shield of Achilles (first in the collection), but the next panel one might see, based on the line of sight, is Shades of Achilles (sixth in the collection). Essentially, this layout allows the viewer to interpret the scenes in any order.

Other important details to note are that the installation begins “in medias res” (a Latin phrase that means ‘in the midst of the plot or story’), and Twombly’s reliance on words and writing contrasts with the oral nature of Homer. Also, the name of the exhibit might seem to misspell Ilium (another name for Troy), but this spelling is intentional—the “A” is a symbolic representation of Achilles’s infiltration of Troy.

In analyzing the work, critics have expressed the idea that any child could paint a series like this one—not an uncommon sentiment in contemporary art. However, not everyone could capture the essence of the Iliad while conveying such strong meaning and evoking great reactions.

In this article, I will examine three paintings in the collection to which I was drawn: Heroes of the Achaeans; Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector; and House of Priam. Generally, the works can be categorized as writing-focused (of which the first and third are examples) abstract art (of which the second piece is an example), or a mix of the two.

Heroes of the Achaeans

Heroes of the Achaeans; Image 2

Throughout the story of the Trojan War, Greek heroes debate who is the “best” of the Achaeans. Though they are important characters, it is not Agamemnon, Odysseus, Nestor, or Ajax—it is Achilles, as this painting shows, because the Greeks cannot sack Troy without him.

Also featured in this image are the names of the gods who intervened in the war. There is a clear hierarchy—the gods appear at the top of the painting (female gods on the left, male gods on the right) and Greek heroes at the bottom.

Zeus is unrepresented here—his name is not on this panel nor elsewhere in the installation. However, everything that occurs in the poem happens according to Zeus’s will, which is also related to the question of fate. Perhaps the absence of his name conveys his omnipresence.

This painting beautifully captures the simultaneous disorder and the restoration of disorder present throughout the poem. It looks chaotic and disorderly at first glance, but ultimately there is an order—everything is intentional by the artist.

Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector

Shades of Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector; Image 6

The red color of Achilles’s shade recalls the fire imagery that describes Achilles in the poem and also refers to his menis, or divine wrath. Twombly incorporates this theme of menis—the first word of the Iliad—throughout all the paintings. By having menis, Achilles assumes a superhuman status. Two examples where he achieves such a status in the poem are in Book 19—when Athena fills his stomach with nectar and ambrosia, the foods of the gods—and Book 20—when the gods have to intervene in combat so that Achilles doesn’t defeat the Trojans before the fated time.

Possessing some of Achilles’s same fiery spirit, Patroclus kills 27 men before Hector deals him a fatal blow. But in Book 16, before he dies, Patroclus is shown to have a softer side for which Achilles ridicules him. In this heartbreaking scene, Patroculus cries because so many of his comrades have been wounded in battle, and he wishes to never have Achilles’s deep-seated anger that has caused irreparable harm to the Greeks. Patroclus’s shade is gray for this reason—not only does Patroclus display a somber emotion, but his tragic death casts a shadow on the narrative. But his gray shade is stained with a slight hue of red—a reminder of Patroclus’s ferocity.

The outline of Hector’s shade is partially erased on the left side, representing how his body sustained damage when Achilles dragged it around the walls of Troy. Hector too, though he is the Trojans’ commander and best warrior, becomes another casualty of the war. It is for this reason that Hector’s shade is colorless and blends in with the background of the canvas. But he is not completely forgotten—the memory of him, of his courage and leadership, lives on even today, as conveyed by the stenciling that remains on the right portion of his shade.

The shape of all three shades underscores the lack of ethnic distinction between Trojans and Greeks—the “Greek” identity has not yet taken shape. Additionally, the consistency of the shape communicates the idea that, Greek or Trojan, everyone ultimately has the same fate: death.

The shape also encapsulates the fact that Achilles’s humanity limits his superhuman qualities—the outline of his human shade confines his red, fiery core.

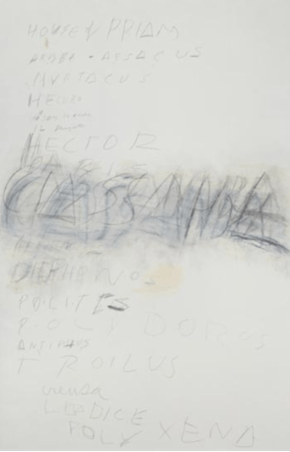

House of Priam

House of Priam; Image 8

Cassandra’s name is the first thing the viewer notices when looking at House of Priam. The smudging and eraser marks indicate how she was silenced—no regard was given to Cassandra’s prophecies because of Apollo’s curse. In Greek society too, women had a reputation for being untrustworthy, especially in their ability to shift alliances from father to husband.

Furthermore, the names of Priam’s children, who all die, remind the viewer about the consequences of war. For veterans, the Iliad represents the soldier’s experience. Both the installation and the poem acknowledge the ruthlessness of war, but kleos aphthiton, eternal glory, is valued so highly that it trumps brutality. These works, however, reflect on and question the morals of war.

Further Exploration

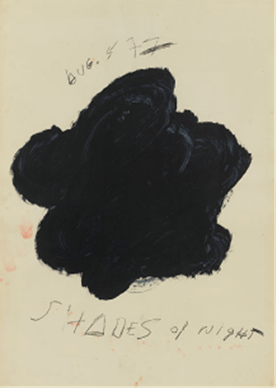

Cy Twombly’s Shades of Night

This article merely scratches the surface of Fifty Days at Iliam. To learn more about the installation, watch this short 10-minute film narrated by John Immerwahr. It uses dramatic music to engage the viewer and weaves the ten paintings together to craft a succinct narrative. Cy Twombly also has other works such as Shades of Night that invoke the same imagery seen in Fifty Days at Iliam—the two works are undoubtedly connected. Finally, to learn more about artist Cy Twombly, check out the book Cy Twombly: Cycles and Seasons.

Lily Nesvold (College ’23) is a student at the University of Pennsylvania majoring in Classical Studies and minoring in Economics.